Three reasons being well-intentioned isn't the defense you think it is

the good, bad and the ugly

(1) The Good

In our regular everyday lives, it’s important to have good intentions. But that’s only because, in our regular everyday lives, we all mostly agree on what’s right and wrong. Don’t take stuff. Don’t hit people. Don’t scam. Etc. We all agree on the good, so the only remaining question is whether you were trying to do that good.

But the realm of politics is different.

Politics is politics because it’s about the stuff where people do not all agree on what’s right and wrong. (And, as I commonly discuss, the beliefs of a movement get baked deeply into the narratives, and sophisticated justifications always emerge.)

In the world of politics, if I do X and you’re against X, then I can’t defend myself by merely arguing that I did X with good intent.

The fact that I think doing X is good is part of my very philosophy. So, saying that I did X with good intent is no more than just saying that I think X is good.

“Of course you did X with good intent! The problem is the very fact that you believe X is good in the first place!” is how a political opponent might reply.

(That’s why I’ve been banging away at those on my own side that, to understand your opposition, you have to grasp that they’re well-intentioned. And that that’s vacuously true, and thus provides no defense. What matters for evil is their principles — and whether they do X — not whether they’re well-intentioned.)

(2) The Bad

Another place where being well-intentioned leaves something to be desired is when a movement moves to punish the unclean out group. Movements do not have good intent toward the unclean out group. No one on the way in the trains to the camps ever said, “At least they’re well-intentioned.”

But you can’t make the mistake of saying as a consequence that they therefore don’t have good intentions. Yeah, not to the out group!

The issue is whether their movement has ethical justifications for their actions — including horrible treatment of the out group. And movements always do. Not necessarily good justifications. They’re often convoluted, irrational and got constructed post-hoc (like how masks became science overnight). But they have them.

And it’s good, in their eyes, to discriminate against the out group; to fire them, to banish them, or to send them to camps.

That’s why righteous sociopolitical movements are capable of evil that even criminal organizations would never be capable of.

(3) The Ugly

Finally, let’s set aside the issue of opposing movements. Let’s just consider one’s own movement.

Since it’s your own movement, well-intentionedness is an issue, as we mentioned at the start. By assumption, all of us within the movement agree on the same notion of the good, but sometimes some of us don’t act in accordance with it, even knowingly.

So, enforcing that everyone within it indeed is trying to adhere to the principles is crucial to the maintenance of the community. That is to say, we must police well-intentionedness.

Suppose that we manage to. We have the perfect situation! I’m in a perfectly well-intentioned community where all agree with me.

Yet, even here, my community is likely to end up behaving very badly.

And the reason is one well known in economics, going back to Milton Friedman.

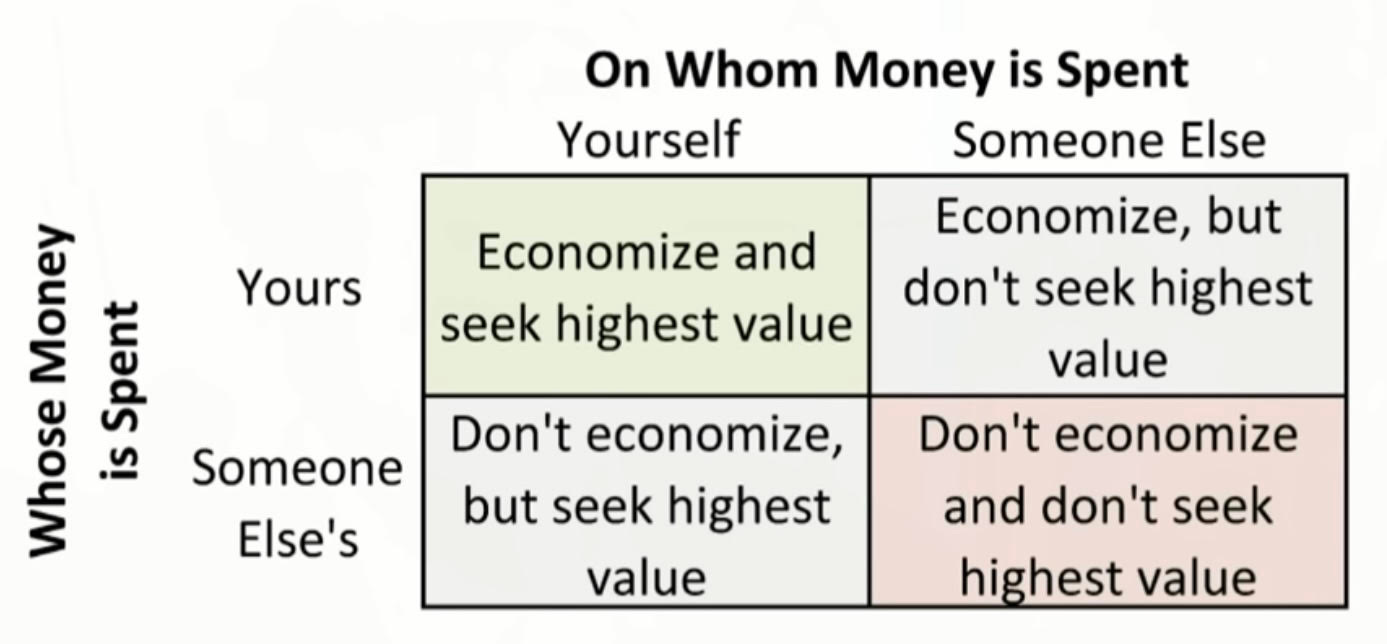

The trouble is simply that, as we’re talking about the behaviors of a large community, the actions of the community will very often — unless it’s a super highly principled libertarian community — be being carried out by leaders who are not simply spending their own resources for themselves, which is the upper left square.

Instead, they’ll invariably be spending the community-at-large’s resources. And they’ll be spending it on the community-at-large. That’s the bottom right square.

Ant that means that — even with their good intentions — they’ll usually blow all their community’s resources, and end up with a result that doesn’t work, and is probably counterproductive.

Sounds a lot like the Lockdowners, huh?

Even by the lights of a Lockdowner fanatic, an honest one must, upon taking stock of the utilitarian outcomes, judge the results of the well-intentioned acts of the movement as a disaster.

Perhaps even… evil.