Human Nature and Politics: Three Lenses, Three Outcomes

Our view of human biological nature isn’t just a scientific curiosity. It deeply associates with our political instincts and the kinds of societies we try to build. The way we imagine ourselves sets the stage for whether we lean toward centralized control, special-essence exceptionalism, or a more emergent, zoocentric outlook.

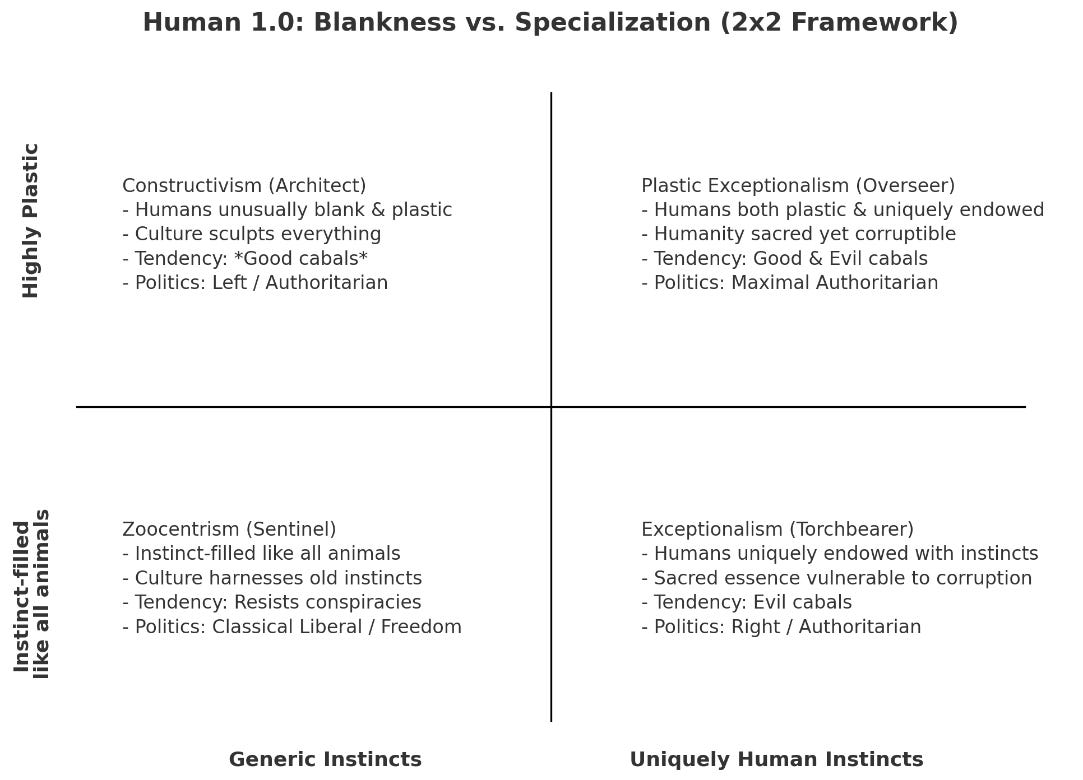

To see this clearly, it helps to map views of human nature onto two axes:

~ Plasticity: To what extent can humans be molded or shaped by outside forces

~ Specialization: Do humans have unique, biologically special instincts that set us apart from all other animals

With these axes in place, three quadrants capture the main traditions of thought:

Upper Left: The Blank-Slate Architect

~ View of human nature: Humans are highly plastic, with no fixed instincts

~ Implication: People are naturally prone to selfishness or destructiveness unless properly shaped. They must be molded by elites, educators, or the state into cooperative beings

~ Politics: This view associates with centralization and top-down control — socialism, technocracy, bureaucratic planning

~ Tendency: Sees virtue as a project requiring deliberate design, often with suspicion toward spontaneous order

Bottom Right: The Instinctual Torchbearer

~ View of human nature: Humans are filled with special, uniquely human instincts

~ Implication: People are naturally good and cooperative, unless corrupted by outside interference. When society goes wrong, it must be the fault of elites or cabals manipulating what is otherwise a virtuous nature

~ Politics: This view associates with traditions of the Right, with emphasis on sacred human instincts, national essence, or cultural uniqueness

~ Tendency: Explains societal failures reductively, by locating evil in particular bad actors rather than in emergent systemic forces

Bottom Left: The Zoocentric Sentinel

~ View of human nature: Humans are instinct-filled like all animals, with nothing biologically special setting us apart

~ Implication: The extraordinary distinctiveness of humans does not come from biology, but from cultural evolution — the “second blind watchmaker” that designs at lightning speed compared to natural selection. Writing looks like nature because culture shaped it; speech sounds like events because culture tuned it; music resonates because culture harnessed perception

~ Politics: This view associates with classical liberalism and respect for emergent orders — free markets, free expression, even science itself

~ Tendency: Appreciates the astronomical powers of decentralization, while also recognizing these same emergent forces produce great societal evils — totalitarian movements, democides, crimes against humanity. Culture can ratchet us upward into Human 2.0, but can also evolve destructive equilibria

~ Analogy: Like heliocentrism in astronomy, zoocentrism gives a more elegant and unifying account: humans need not be a special case to explain our extraordinary trajectory

The blank-slate Architect and the instinctual Torchbearer each try to explain modern humanity by stuffing the explanation into the individual — as if each person has a special reductive property that accounts for our uniqueness. But both struggle with emergence.

The zoocentric Sentinel instead emphasizes culture as an autonomous evolutionary force that takes ordinary animals and, through decentralized dynamics, generates astronauts, civilizations, and science.

And because these views of human nature associate so closely with political outlook, a false picture of what humans are means drifting into one of the camps that forever fuel strife.

A clear-eyed understanding of Human 1.0 as instinct-laden animals — and of Human 2.0 as the cultural harnessing of those instincts — pulls us toward freedom, toward decentralized emergence, and toward the civil liberties that allow cultural evolution to keep running, compounding, and lifting us further upward.