Extending the Circle of Thirds to the Dozen Directions Dial

WARNING: Only for music theory nerds

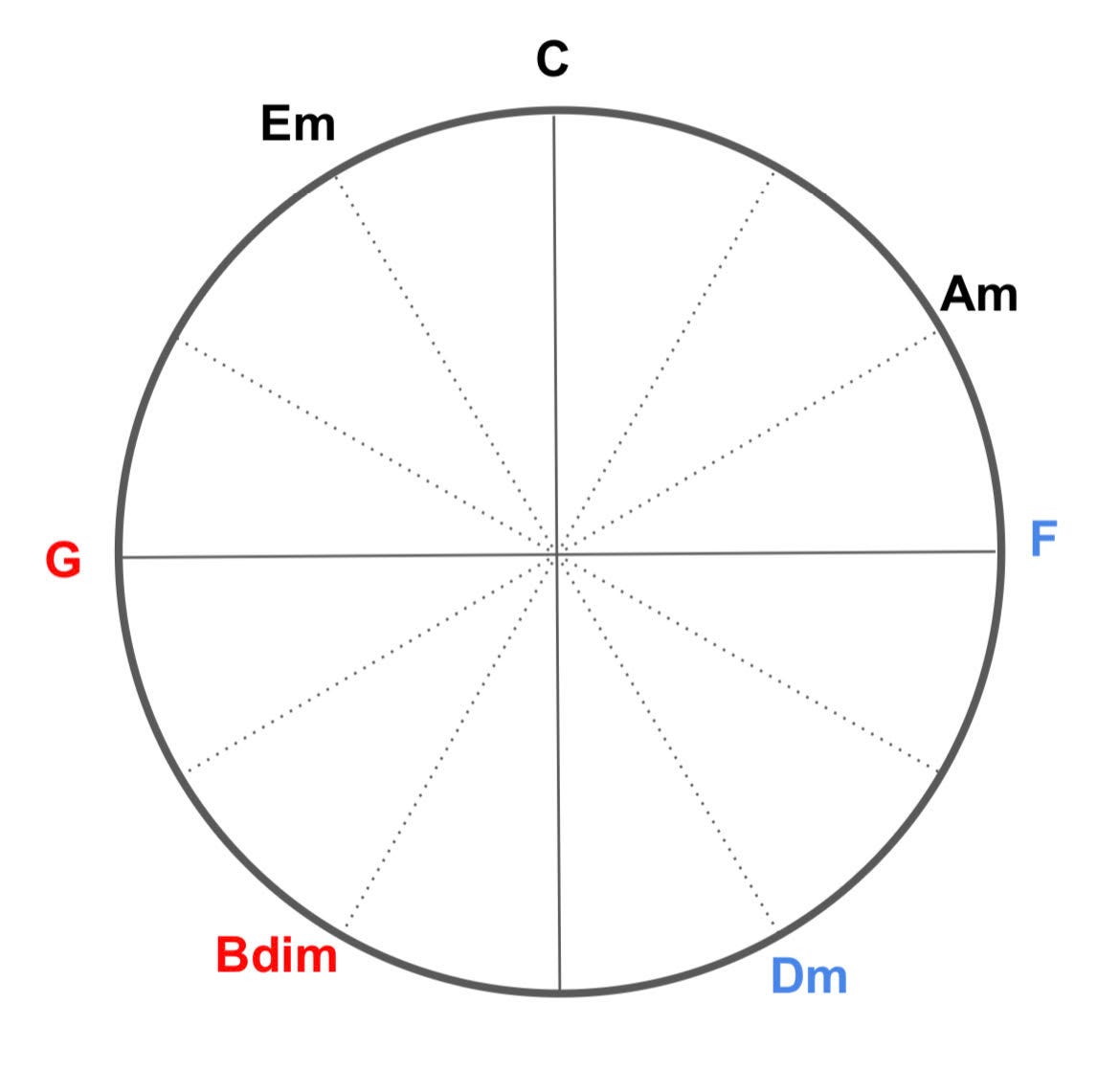

In a recent article (search on “Each musical chord tells your brain the direction of a person moving evocatively in your midst”) I derived this diagram below.

In my earlier book HARNESSED I have argued that music culturally evolved to sound like a human moving evocatively in your midst. The signature sounds of music have all the signature sounds that humans make when they move.

But more recently I have re-entered the space, trying to crack the code behind chords and chord progressions.

And, in that recent article I referred to, my claim is that when your brain hears these various chords within a key, it associates these as informing it about the direction of the human mover.

I won’t get into the detail here for why, and, at this point this facet of the theory is not well worked out.

But, in this post I wanted to point out something interesting for those who have an eye for music theory.

One thing about the space above is that it’s the Circle of Thirds, but, not quite. Rather than the thirds being uniformly distributed around the circle, in that earlier article I motivated why the thirds are NOT uniformly distributed around the circle, and are, instead, distributed as shown there. Some chords are closer to others, and this is simply due to the chords being more similar, but also crucial to understanding the way our brains interpret the chords: as a direction of a mover.

Anyhow, to keep it on music theory and not on the origins of music, now that we see that the thirds are not uniformly distributed around the circle, we might naturally wonder what chords fall into the gaps?

Well, as a first answer, they’re not chords within the key (of C, in these examples). They use black keys, and so aren’t “allowed” in the sense of keeping ourselves within the key.

Nevertheless, it’s useful to gander at the gaps and see what they are. …without any over-arching moral on my side yet, I’m afraid. …other than that it’s new to me.

The gaps are unambiguously filled by certain chords (although some of them can have multiple equivalent names), because to get from chord in this almost circle of thirds diagram there is always one note that must be moved to a black key, thereby bringing it half way to the next third.

In this diagram I have all the gaps filled in. (As well as using more general notation in parentheses, which you can ignore.)

So, for example, C+ (which is a C chord with the G-note raised to G sharp) is, so the theory claims, associated with 30 degrees angle of direction difference than the C chord.

And, although the Circle of Thirds has no opposite direction for C, in this rule-breaking diagram here (rule-breaking in the sense that now there are five chords that break out of the key with one note), B flat is the opposite of C, i.e., associated with going in the opposite direction.

One can now create songs with a chord progression of 12 consecutive chords, making the full circle, and that should sound like a very slowly turning mover. It’s probably not much used in actual chord progressions, though, because it breaks out of the key, and leads to more dissonant harmonics.

Here’s an updated variant of it