Ethics Don’t Divide Us — Hallucinated Facts Do

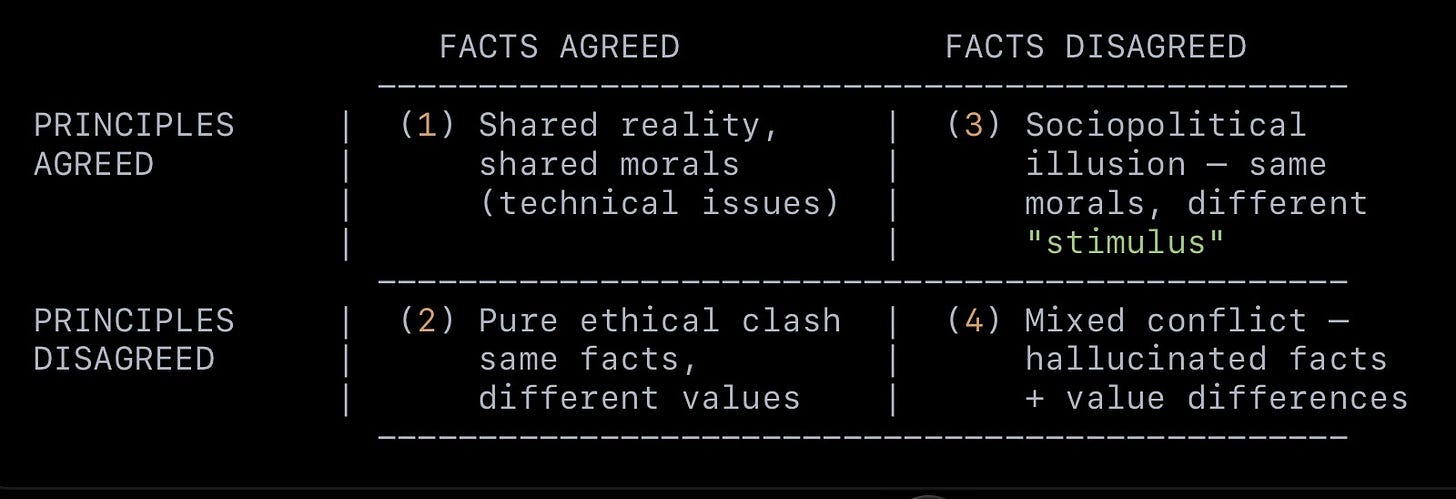

[This article is about the top right case above]

Most people imagine ethical disagreements as cases where everyone accepts the same facts but applies different moral principles, yielding different conclusions. In perceptual terms, this is like the classic rabbit/duck illusion: two observers may “see” different things, but they still agree on the strokes on the page — the underlying data. These are ambiguity illusions.

But there is a more profound kind of illusion, the geometrical ones — like the Hering — where the brain doesn’t just choose between interpretations of the stimulus; it perceives a stimulus that isn’t there at all. The vertical lines are physically straight, yet the visual system sees them bowing outward. This happens because perception is functional and forward-looking, anticipating what the world will look like by the time the percept is constructed. These are “inconsistent illusions,” because the perception is not even consistent with the data.

Real-world ethical disagreement during manias is very often of this second kind. Sociopolitical communities don’t typically begin by examining shared facts and applying different principles. They begin with a distinctive ethical “perception” — usually a membership signal — and only then reshape the “facts” to make that ethical perception seem justified. Once the facts have been rewritten, they can use the same principles their opponents hold and still reach the predetermined conclusion. It isn’t…

same facts + different principles → different ethics;

it’s…

different facts + same principles → different ethics.

The COVID mask mania is a clean example: “masks are good!” began as a membership signal at a time when the actual evidence and expert advice said otherwise, but once it mattered socially, communities generated a cascade of post-hoc “studies” so that the facts would appear to support the prior moral position — allowing them to claim ethical consistency without changing any principles. Membership signal culturally evolved into virtue signal.

Likewise, the immediate “genocide” cry on 10/7 functioned first as a declaration of allegiance, and only afterward did its adherents selectively reinterpret events, quotes, and casualty numbers to construct a world in which genocide simply had to be occurring.

In both cases, the ethical principles never changed; the perception of the facts did. And once the world is perceived differently, the moral conclusions follow automatically.

Learn more about why we see illusions and my seminal discovery that we see them because our brains are anticipating the near future, in my book, Vision Revolution.

Also my TED… https://www.ted.com/talks/mark_changizi_why_do_we_see_illusions