Each musical chord tells your brain the direction of a person moving evocatively in your midst

This is part of a continuing series of articles on my new research on the origins of music. See my earlier book, HARNESSED, and this previous post (just below) focusing on the vocalization facet of it. I now think that that’s probably a side effect of the deeper foundations in the sounds of human movement, something I’ll begin getting toward here, and in upcoming videos and posts.

As a reminder, the motivation for my re-entering the world of the foundations of music was that I recently learned, or at least finally absorbed, the idea that all the seven chords within a key can be placed into three equivalence classes. In the key of C, they are…

Tonic: C, Em, Am

Subdominant: F, Dm

Dominant: G, Bdim

And, they’re supposedly kinda sorta “equivalent” in some intuitive sense, namely, that when you play any within the same class, you feel that the music hasn’t much shifted in “direction” or “tension” or… something.

Now, as a backdrop, in my earlier book, HARNESSED, I argue that music culturally evolved to sound like humans moving evocatively in your midst. In that book I explain loads of things about music, but not chords, chord progressions, etc.

That there might be three equivalence classes among the chords within a key suggests that there might be something much simpler going on, and much lower dimensional. If there are only three classes, maybe the dimensionality is only three, and not seven. Or maybe even lower (as we will see). And that would be a theory game changer, because most of us are incapable of doing mental rotations in seven dimensional space!

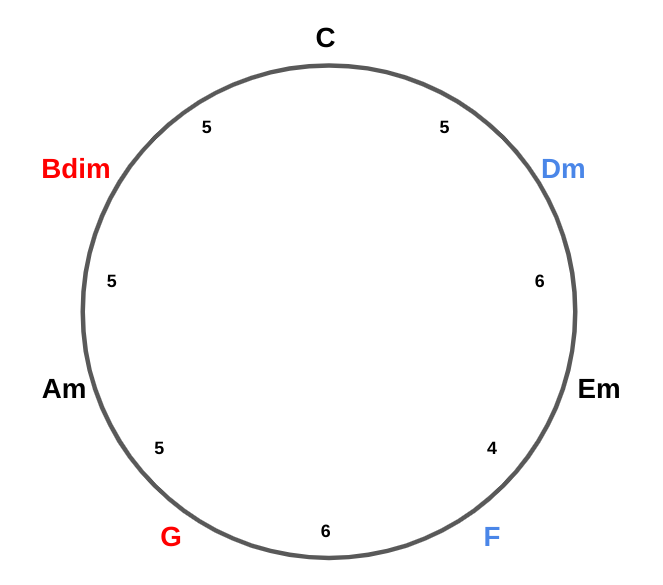

Here are the seven chords, shown adjacent to one another around the octave loop. With tonic, subdominant and dominant labeled as black, blue and red.

Looking at this, one wonders…

Going in either direction starting from C, notice how it goes from tonic to a different color, back to tonic, back to that same color again, but then suddenly flips to the new color at the bottom.

So, for example, along the right side, it goes: black, blue, black, blue, but then suddenly to red.

That’s weird. We have small note-changes on the piano, moving from chord to adjacent chord, and so the question is, What might be happening at a deeper level that could explain why it would toggle between black and blue twice, and then switch to red?

Here’s a driving intuition:

When we move from one chord to an adjacent chord, I claim that the “meaning” in some underlying space is approximately the opposite. I’m claiming that now just so that we can explain this weird toggling that suddenly doesn’t toggle that I just mentioned above.

But -- and this is key -- to explain this weird toggle phenomenon, I am going to suggest that, when going from one chord to the adjacent, it doesn’t necessarily go to the FULLY opposite, but something that is only approximately the opposite. This will help us “explain” why, after “flipping” nearly to the opposite a couple times, when it approximately flips again, it’s -- by then -- pointing in a qualitatively new direction than where it started a couple toggles before.

(Note: I happen to think this underlying space will concern direction of movement of a human moving in one’s midst, the thesis of my earlier book, HARNESSED, but let’s set that aside for now, and just look at what kind of structure the meaning needs to have to get this weird toggling.)

Now, in this light, how can we tell, in moving from one chord to the adjacent chord in the key, how much the meaning has flipped toward the opposite (in some supposed underlying space with some eventual nice interpretation)?

As there are seven chords, perhaps, in moving from a chord to the nearest chord, the meaning flips not directly to the 180 degree opposite side, but, because there are seven -- which can’t be uniformly spread around a space and have perfect opposites -- it has to be a little less (or more) than that.

Among even fractions of 7, 3/7 is the closest to to half way around, or (3/7)*180deg, which is about 150.7 degrees.

So, a thought is that, in some true underlying space, we imagine that, in moving from a chord to its adjacent chord here in this diagram in Figure 1, in the true underlying space it’s moving to 150.7 degrees in the kinda opposite direction within that space.

Now let’s build the new underlying space, supposing that each time we move from chord to adjacent chord in the previous diagram, that that new chord is 150.7 degrees (or, “kinda opposite in meaning”) around the circle from the previous.

…and… this is what we get above.

This space is just the well known circle of thirds, where one moves sideways on the piano from chord to chord, but skipping a chord each time.

Key for us, though, is how we arrived at this circle of thirds space. It is what one gets when trying to resolve why the tonics, subdominants, and dominants are so weirdly interspersed around Figure 1. My idea for solving that weirdness led to assuming that going from chord to adjacent chord is an “almost opposite” in the underlying space, and that turns out to lead us to the circle of thirds, where the three classes end up nicely clustered, the weirdness all gone.

Indeed, when done in this way, the resultant space now clusters the three classes together, tonics upward, subdominants southeasterly, and dominants southwesterly.

That is, IF it were the case that the underlying “real” space is such that, when moving from a chord to its adjacent on the piano (i.e., in the first diagram), the direction changes to close to its opposite (but not actually the opposite), then the three different classes — tonic, subdominant (blue) and dominant (red) — end up clustered separately in their own regions.

And, once we get the chords in this true space (in Figure 2), we don’t really need the colors at all. G and Em would have their own similarity in being leftward-directed, for example, despite G being a dominant and Em being a tonic. Point being is that this space preserves the intuitions we started with, but generalizes quite beyond them.

As I hinted earlier, my guess is that the meaning of this space is the direction of the mover, which is the thing making the chord sound (the chord representing its fundamental pitch and key harmonic vibrations).

So, opposite in this space means moving in the opposite direction.

AND, the idea would be that, in moving from one chord to an adjacent chord (in the earlier diagram in Figure 1), one is roughly moving each note up about two semitones (not always, and more on this later), and so the idea is that, for humans, that tends to indicate approximately a full 180 degree change in direction. (A “semitone” is just a single step on the piano, from a note to the very adjacent note in either direction.)

(Now, actual human movement induces Doppler shifts much smaller than a semitone, but the idea here is that the fictional mover in the song has an exaggerated speed, and a consequent Doppler shift from high to low of two semitones.)

For example, in going from C to Dm, although adjacent on the piano (and thus the earlier diagram), the change in pitch is consistent with the mover having changed direction by nearly 180 degrees (due to the Doppler shift). But, not actually a full 180 degrees; only about 150.7 degrees instead. And thus we see it way down, but on the right a bit.

In moving from Dm to its adjacent, Em, that, too, is about 150.7 on the other side, and so Em is at the upper left.

And so on.

Let’s go back to the first diagram in Figure 1, the one with the chords placed according to their nearest neighbor on the piano. But, now I have placed the number of semitones for each note one has to move in shifting from chord to the next.

The idea in Figure 2 was that, in moving from a chord to its adjacent chord on the piano, it goes approximately to the opposite side within the real space, and that led to our being able better capture the space: The distinct types of chord ended up clustered together (in Figure 2), rather than weirdly interspersed (as in Figure 1).

But, the idea of going 3/7 away around the circle was just based on there being 7 chords that must be distributed around the space, and 3/7 was as close to half way as you can get using whole number ratios.

There is reason, however, to think that we can get more precise with which angle, in particular, each chord-to-chord piano transition means.

In moving from C to Dm on a piano, the minimum number of semitone shifts one must do is 2-1-2 (for each finger, respectively). That is, for the notes, the C-note goes 2 semitones to the D-note, the E-note goes 1 to the F-note, and the G-note goes 2 to the A-note.

In the diagram in Figure 3 I have placed all these shifts, in this notation.

Now, in Figure 4, the semitone shifts are just summed together to make it easier to digest the whole diagram.

(Notice as an aside that, although we have seen a beautiful left-right mirror symmetry for the three equivalence classes thus far, when we include these “# of semitone shifts” that symmetry is broken. Instead, Bdim happens to be privileged, at one end of the symmetry line shown below (which ends in between Em and F on the other side). I don’t have any insight on this yet.)

With these semitone shift numbers, we can get more specific on how far in the opposite direction a shift from chord to the adjacent one is.

The greatest semitone shift a chord-shift can be here is 6 semitones. Larger shifts in semitones imply a larger overall change in the underlying space (and, I suspect, in the direction of the mover).

So, let’s suppose that that (i.e., 6 semitones) corresponds to exactly 180 degrees in the true underlying space.

That then means that those chord shifts having 5 semitones are ⅚ 180 degrees, or 150 degrees. And the one case of 4 semitones (between Em and F) is ⅔ 180 degrees, or 120 degrees.

4 → 120 deg

5 → 150 deg

6 → 180 deg

So, in the next slide, we’re going to convert ourselves into the underlying meaningful space again, but rather than saying that -- in going from C to Dm -- that Dm is 150.7 degrees on the other side, we’ll say it’s exactly 150 degrees. And, for Dm to Em, that will be 180 degrees (because it has six semi-tones between them). Etc.

So, here’s the space, but with much more specific locations given the rules in the previous slide concerning the number of semitone shifts for each transition.

Since all the shifts were 120, 150, or 180, we can divide the space up into 30 degree intervals.

Starting with the C-to-Dm transition, recall that that had 5 semitones, and so must be 150 degrees around the circle, which is where it is here.

Then, for Dm-to-Em, that transition was one of the two cases of a 6 semitone shift. And that means Em is exactly opposite of Dm, as shown.

Now, for Em-to-F, that’s 4 semitones, and so ends up 120 degrees, or now perfectly pointing east.

G-to-F is 6 semitones, and so G is pointing west.

G-to-Am is 5 semitones, and so Am is 120 degrees on the right.

Finally, Am-to-Bdim is 5 semi-ones, and so Bdim is down left, symmetrical with Dm.

Interestingly, each of the seven chords has a specific direction in the space.

And C, F and G are prime directions, somewhat justifying the reasonableness of this theoretical development. (…because C, F and G — or I, IV, V — are the backbones of chord progressions.)

And notice that now they are not uniformly distributed around the circle, but still have the general pattern we saw in our first approximate “3/7” (or 150.7 deg) idea (Figure 2), with tonics generally north-ish, subdominants southeast, and dominants southwest. That is, this is no longer just the circle of thirds, but a circle with specific spots of each of them, and they’re no longer uniformly distributed.

C and Em end up 30 degrees apart here, and that would suggest that -- if 6 semitones corresponds to 180 degrees -- C and Em differ by just one semitone. Is that right? YES: We can get from C to Em by just shifting the C-note to a B-note. Only one semitone change is required, which is why C and Em are very close in direction in this space.

Same for Am and F: F can change to Am by just shifting the F-note to an E-note..

This also helps us realize that the very idea that there were three equivalence classes was just a very rough idea, and not quite right.In the scheme here, we can see that Am and F are actually more similar to one another than is Am and C.

Yet, Am does have the key C-ish feature, namely having a northerly component.

Now, my suspicion, again, is that the brain’s interpretation of these chords is that the mover is moving in these directions.

I’m not yet sure which direction relative to the listener a C chord implies, but I’ll presume it’s moving orthogonally, with no Doppler shift. (That is, not moving closer or farther from the listener.)

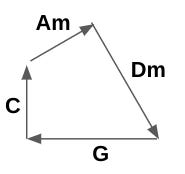

What makes a good chord transition, one that is repeatable, is one where the vectors add to get approximately back where one began.

So, for example, one of the most common is…

C-Am-Dm-G

Here is its vector diagram…

The chord transition is telling us about how, in this case, the mover is moving in a loop, one with these general trajectories.

Now, the reason that a song that just hangs out among the three tonics, say, is not generally desired is that it just basically describes the person moving forever in about the same general direction. He or she never comes toward you. (Or, it might sound as if you yourself are moving along with the person, with only slight changes in distance between you and him. No loops. Maybe this is what funk is about, which often has unchanging chords.)

Same for any overuse of any of the chords near one another.

The key to a good chord transition is, I think, about having the chord-making mover transition into an interesting sequence of directions, sometimes toward you, sometimes away, looping the other way, and so on. …and probably such that it finds itself in a loop. It doesn’t need to be a perfect loop, but probably that will be a common theme, lest it not be repeatable.

More coming! If you like LooFWIRED’s mix of science and philosophy and anti-authoritarianism, consider becoming a member.