Covid Crowd Tyranny

Back in March 2020, before the first lockdowns were rolling out, I pinned a tweet that read:

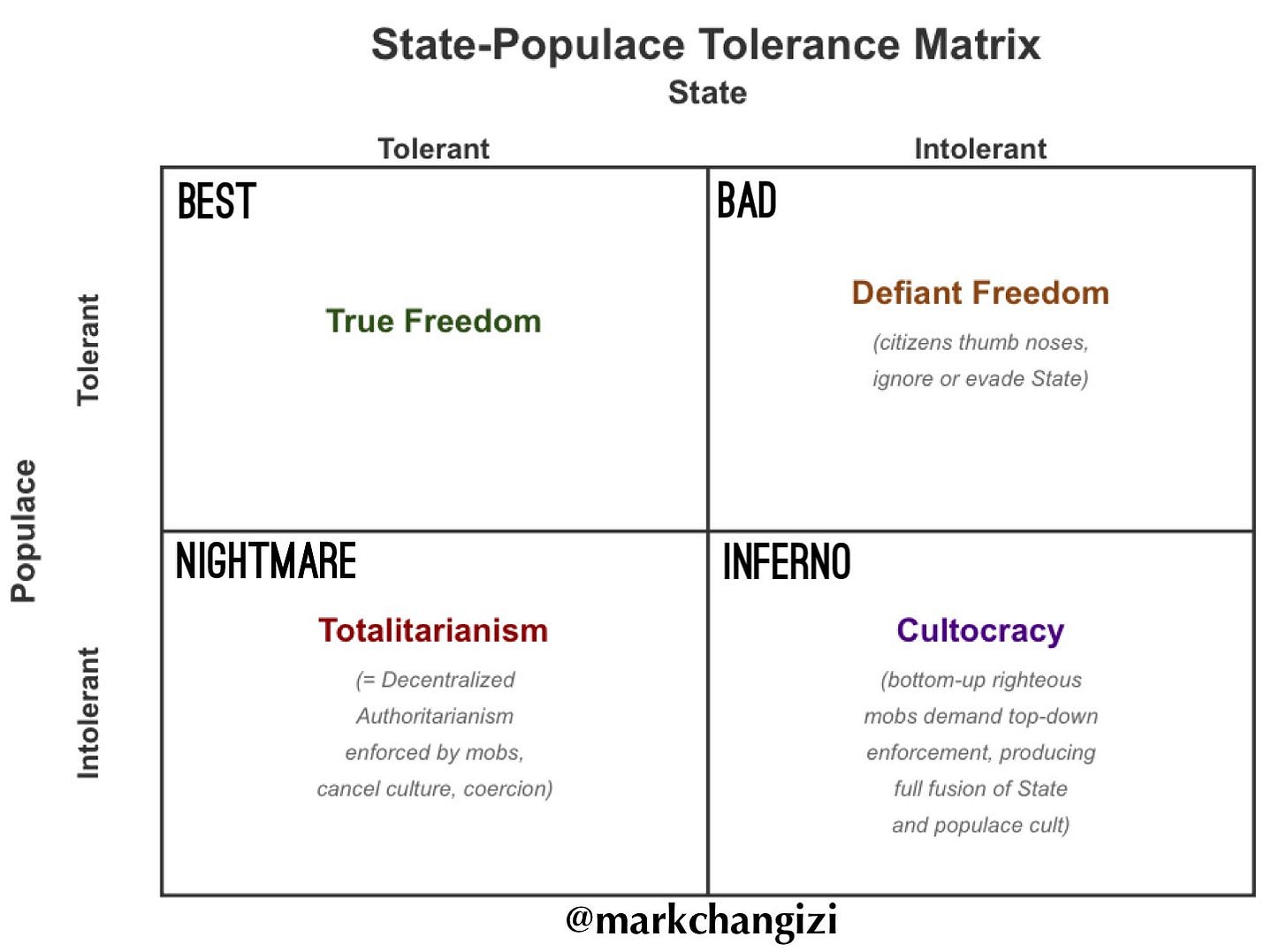

That turned out to be prophetic. COVID-era authoritarianism felt to many like the heavy hand of the state, but from the start it was clear that something subtler—and in some ways more disturbing—was taking shape. The real coercive force didn’t come from government agents but from ordinary citizens, employers, and institutions acting as enforcers of a moral consensus. From the very beginning, I noted that the pandemic’s social climate fit the bottom-left quadrant of the State–Populace Tolerance Matrix (below): an intolerant populace within a relatively tolerant, or at least hesitant, state.

Few people were ever fined or arrested for refusing to wear a mask. Police rarely demanded vaccine cards. Yet millions of citizens behaved as though such punishments were imminent. The fear came from neighbors, coworkers, HR departments, and social-media mobs. A maskless jogger could be yelled at in the street. A nurse could be fired for declining the vaccine. Restaurants and airlines imposed restrictions well beyond what law required. The public didn’t wait for the state to enforce orthodoxy; it enforced it on itself.

That, I’ve argued, is the true character of totalitarianism. My hypothesis is that what people have long called “totalitarian” regimes are not primarily top-down systems of control, but decentralized authoritarian networks—societies in which ordinary citizens themselves become the agents of enforcement. The state merely gestures, and society eagerly supplies the teeth. Governments issued guidance, but moral fervor and reputational fear did the real work. The impulse to appear virtuous—to demonstrate loyalty to “The Science,” to protect others, to belong—created a moral economy that punished dissent more ruthlessly than any statute could.

It’s useful to remember what pure top-down enforcement actually looks like. Consider highway patrol. The state formally sets a 55-mile-per-hour limit, but nearly everyone drives 65 or 70. Officers occasionally ticket a few unlucky drivers to remind the rest of us of the rule, but most of the time we all “break the law” together without shame or fear. That is classic top-right-quadrant behavior: an intolerant state but a tolerant populace, where citizens quietly ignore intrusive rules. COVID was almost the mirror image—citizens zealously policing one another while the state largely watched.

There were moments when the line blurred and the system slid toward the bottom-right quadrant, where state and populace intolerance fuse. Australia’s police crackdowns, Canada’s freezing of protester bank accounts, and the occasional American governor threatening fines for gatherings all hinted at full-on cultocracy. But these were exceptions. Even in those cases, the energy came from below—the crowd demanding that the state punish heretics on its behalf.

That is why the period was so unsettling. It revealed that formal authoritarianism is almost unnecessary once enough citizens internalize the urge to police one another. A dictator’s dream is a populace that enforces tyranny voluntarily. COVID showed, in real time, how close even liberal societies can come to that condition—not through government decrees, but through a contagion of moral certainty.